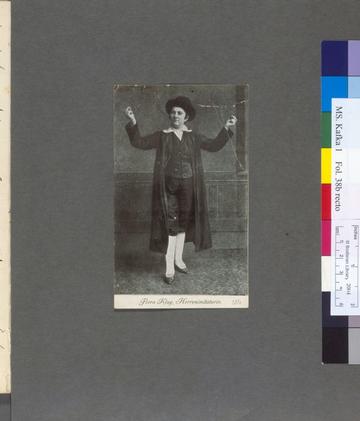

Flora Klug, Gentleman Impersonator

Niamh Devlin holds a first-class MA (joint honours) in Philosophy/Theology & Religious Studies from the University of Glasgow and spent part of the summer of 2022 on a UNIQ+ research internship working with the Oxford Kafka Research Centre.

Figure 1: Photograph of Flora Klug, ‘Herrenimitatorin,’

(c) Bodleian Library, University of Oxford - MS Kafka 1, fol. 38b

Kafka’s interest in the Yiddish Theatre in Prague is a familiar topic within Kafka studies. Commentators usually focus on Jizchak Löwy in relation to Kafka’s engagement with the Yiddish theatre, thus perhaps overlooking other significant actors. One example of this is Flora Klug (1886-1964). Flora was a female actor in the theatre who specialised in performances in which she played male roles – similar to what we would now characterise as drag performances. Despite her masculine presentation in the theatre, she was not immune from the typical fate of many women in history; disregard, resulting in her disappearance in historical records. With little biographical information preserved, it may seem odd to dedicate a blogpost to her. However, Kafka frequently writes about Flora, or ‘Mrs. K’ in his diaries, demonstrating a strong intrigue he had toward her. We can use these diary entries alongside reviews of her performances, and the sparse biographical information that we do have, to construct an insight of her entrancing and bold persona. In doing so, speculation into Flora’s impact on Kafka’s writing will come to the fore, thus revealing how Flora Klug – a star in her own right – deserves further attention in Kafka studies.

As previously mentioned, Flora’s notoriety came from her talent in performing as male characters. This was not wholly unusual in the Yiddish theatre – other women who took on male roles included Fraydele Oysher, Marilyn Michaels, and Peni Littman (Seigel, n.p.). Flora is not the only female actress performing a male role that Kafka writes about in his diaries; for example, he writes about watching Frau Libegold in Joseph Latteiner’s David’s Fiddle (Shahar 226). Considering the relevant context these women came from (i.e., participation in a domain historically occupied exclusively by males, and despite traditional orthodox Judaic teaching prohibiting men watch women sing or perform), such gender-diverse presentations can be characterised as reactionary (quasi-)feminist performances that allowed them to achieve success and notoriety for their talents (in spite of their traditional ascribed role as homemakers and their other familial burdens (Quint, n.p.)). While such perversion of traditional presentations of gender were not unconventional within the Yiddish theatre, it was uncustomary to many of their audience members. Kafka was a part of such a confused collective, capturing such bewilderment in his diary; ‘I really don’t know what sort of person it is that she and her husband represent’ (5 October 1911).

However, that is not to say that Kafka held such gender-disruptive performances in disfavour. In fact, he seems to have been engrossed with the fluidity of Flora’s gender presentation. For example, after watching her perform on 4 October 1911, when she was dressed in traditionally Chassidic costume (more on the relevance of this later), she adopts a virtually genderless identity; ‘”Male Impersonator” [Herrenimitatorin] is really a false title. By virtue of the fact that she is stuck into a caftan, her body is entirely forgotten’ (October 8, 1911) (Gilman 195; Korbel 124). However, this androgynous demeanour is not rigid. For example, Kafka also came to know Flora outside of the theatre, where she took on the feminine roles of mother and wife, which he also records in his diary, such as on 1 November 1911 when he records bidding farewell to Flora and her husband, Süssand Klug, in which he seems to present a particular dislike towards her spouse, (‘all he can do is open his mouth wide and bitterly and then snap it shut, as though forever’) perhaps rooting from jealously and his heightened awareness of rejection; ‘The first impression I had at the performances, that she [Mrs Klug] did not like me especially, was probably correct.’ The way Kafka captures being in Flora’s presence does imply a level of attraction toward her, though he also mentions how he was attracted to her ‘staging a man,’ implying an interest in the way in which Mrs Klug presents gender with such variance. (Korbel 124). Such fluidity fundamentally disrupted Kafka’s previous rigid understandings of gender (rooted in traditional Judaic teaching), potentially presenting itself in the way Kafka presents gender in his fictions as ‘in flux and indistinct’ (Lorenz 169).

Another crucial aspect of Flora’s performances was not only the masculine presentation, but the adoption of a traditionally Hassidic identity through clothing; not only was Flora physically recognisable as masculine, but recognisably Jewish (Gilman 195; Korbel 124). However, the variant of Judaism purported by her costume was not the Western assimilated identity, but the ‘exotic’ Eastern presentation of Judaism. Accordingly, we can gather that Kafka was taken aback by this particular physical, ‘alien’ characterisation as a Chassid (Ultra-Orthodox Jew) that he wrote about in his diary on 5 October 1911:

Mrs K., ‘male impersonator’. In a caftan, short black trousers, white stockings, from the black shirt a thin white woollen waistcoat emerges that is held in front at the throat by a knot and then flares into a wide, loose, long, spreading collar. On her head, confining her woman’s hair but necessary anyhow and worn by her husband as well, a dark, brimless skullcap, over it a large, soft black hat with a turned up brim.

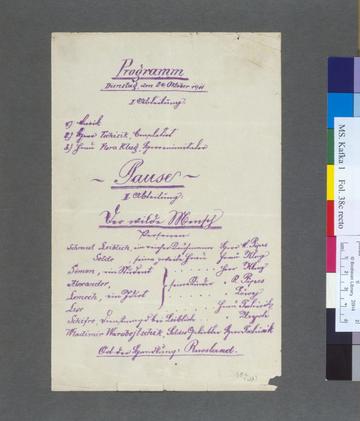

Figure 2: Theatre programme mentioning Flora Klug.

(c) Bodleian Library, University of Oxford - MS Kafka 1, fol. 38c recto

This was not an isolated event: as alluded to earlier, Flora specialised in these gender-diverse performances, specifically those where she presented herself as an Ultra-Orthodox male, Kafka watched them and wrote about them in his diaries several times. For example, in another diary entry dated 6 January 1912, Kafka describes ‘the tightly twisted curls at her temples’ (payos) thus reinforcing this idea of ‘authenticity’ and ‘pure’ ultra-orthodox presentation of Judaism. Accordingly, while Flora Klug unsettled Kafka’s rudimental understandings of gender, her performances reflecting traditional Hassidic costume and costumes reinforced his (problematic) understanding of ‘authentic’ Judaism. That is, Flora’s appearance in the theatre served as a physical manifestation of the cultural authenticity that he had purported on the Eastern Jews. Descriptions of Flora’s appearance, with an emphasis on hair, head/face, and ‘foreign’ clothing are very similar to Kafka’s other allusions to such Jewish ‘authenticity’ (i.e., In Our Synagogue and the diary entry from 14 September 1915; the focus of my previous blog post). The irony behind this sentiment cannot be ignored. Flora was actively performing such ‘authenticity’; the features behind such Eastern and ‘exotic’ authenticity was not necessarily authentic or natural to these Jews of the theatre troupe; as Miron writes how the ‘refined Western intellectuals’ were fascinated by the actors’ glued-on beards and Hasidic clothing (Chapter 14/paragraph 6.100).

However, a unique element of Flora’s manifestation of Kafka’s understanding of ‘authenticity’ is the way in which she united the Jewish individuals into a community. Most of Kafka’s diary entries on the matter of authenticity are recounted from the perspective of an alien outsider, but his entries on Flora highlight the inclusion and establishment of community she maintained. For example, originally unfamiliar with the Yiddish songs of the theatre, Kafka comes to feel connected; ‘I sang the tunes with her, later the words’ (November 1, 1911) (Bruce 34). Further, on a diary entry dated 5 October 1911, he specifically outlines her aptitude in this sense as deriving from her Jewishness; – ‘because she is a Jew, draws us listeners to her because we are Jews.’ Many understand her unification of her Jewish audience as being the inspiration behind Josefine in Josefine the Singer; her singing and performing evokes strong emotion in the community, bringing them together. It makes sense that the complicated character of Josefine was inspired by another complex persona. The claim is also strengthened by the fact that we know that the Yiddish theatre profoundly impacted Kafka’s writing more generally, including the very notion of ‘performance’ and an awareness of the power of moment and gestures (Stach 56). As Shahar puts it, the Yiddish actors provided Kafka with ‘a new aesthetic mode’; a fluid one without the fixed boundaries and identities of Western Jewry (227). Thus, not only do we find this sense of fluidity again as we did with gender, but a strong association with how such boundless identities operated within the united group identity of ‘authentic’ Eastern Jewry.

To conclude, despite the limited biographical information available on Flora Klug, we can understand her significance as a successful actress with an enigmatic allure, disrupting Kafka’s pre-existing understandings of gender while reinforcing his understandings of ‘authentic’ Judaism. Her legacy consists almost only through limited reviews of her performances, Kafka’s diaries, and her possible incarnation in the figure of Josefine, perpetuating a desire to learn more about her, leaving us empathetic to Kafka’s position in relation to her brilliant persona.

Works Cited:

Gilman, Sander L. Franz Kafka. Reaktion, 2005.

Kafka, Franz. The Diaries of Franz Kafka, 1910-1923, edited by Max Brod. Hammondsworth, 1964.

Korbel, Susanne. ‘Popular Entertainment in Central Europe as a Space for Jewish and Queer Migration Experiences.’ In Queer Jewish Lives Between Central Europe and Mandatory Palestine: Biographies and Geographies, edited by Andreas Kraß, Moshe Sluhovsky and Yuval Yonay. Transcript Verlag, 2021, pp. 110-130.

Massino, Guido . ‘Franz Kafka’s Vagabond Stars.’ Digital Yiddish Theatre Project, October 2016, https://web.uwm.edu/yiddish-stage/franz-kafkas-vagabond-stars

Miron, Dan, and Yitzhak Lewis. The Animal in the Synagogue: Franz Kafka’s Jewishnness. Lanham, 2019.

Quint, Alyssa, and Amanda (Miryem-Kahye) Siegel. ‘Women on the Yiddish Stage: Primary Sources.’ Digital Yiddish Theatre Project, November 2021, https://web.uwm.edu/yiddish-stage/women-on-the-yiddish-stage-primary-sources

Seigel, Amanda (Miryem-Khaye). ‘Top 10 Queerest Moments in the Yiddish Theatre: An Illustrated List in Honor of Pride Month 2019.’ Digital Yiddish Theatre Project, June 2019, https://web.uwm.edu/yiddish-stage/top-10-queerest-moments-in-the-yiddish-theater-an-illustrated-list-in-honor-of-pride-month-2019

Shahar, Galili. ‘The Jewish Actor and the Theatre of Modernism in Germany.’ Theatre Research International 29.3 (2004): pp. 216-31.

Stach, Reiner. Kafka : The Decisive Years, translated by Shelley Frisch. Princeton University Press, 2021.