On a 1983 Kafka Exhibition in Oxford

Kafka has played a central role in the cultural life of Oxford for several decades. One important milestone was the centenary of Kafka’s birth in 1983, which the Bodleian Library marked with an exhibition dedicated to him. The richly illustrated catalogue describes an exhibition of two parts and with a dual focus.[1] One part, ‘From Pen to Print’, was on display in the exhibition room in the Bodleian’s old school quadrangle from 10 May until 25 August 1983; the second half, ‘Paths out of Prague’, was hosted by the Taylor Institution, home of the University’s Modern Languages collection, and on display from 10 May until 17 June. The exhibition flyer also lists an opening event on 9 May, namely ‘a selection of films seen by Kafka’ screened at the Taylorian and presented by the German director Hanns Zischler, who later went on to publish his findings in his 1996 monograph Kafka geht ins Kino.

The exhibition was organised by Malcolm Pasley, Fellow in German at Magdalen College Oxford. In their joint preface to the accompanying catalogue, Giles Barber, Librarian of the Taylor Institution, and John Jolliffe, Bodley’s Librarian, start off by play devil’s advocate; though Kafka is an author of international standing, they nonetheless raise the question ‘why the centenary of the birth of this particular German-language author should be marked by a double exhibition in Oxford’. In answering this question, they refer to a second, more poignant anniversary: 9 May 1983, the eve of the exhibition’s opening, is also the fiftieth anniversary of ‘the inauguration in Nazi Germany of the public burning of officially disapproved literature’, which would have included the works of Kafka (5). In referencing this much darker anniversary, the authors draw a poignant dual analogy both with Kafka’s own disregarded instruction to burn his unpublished writings and with the ‘world conflagration’ which was caused by Nazi rule. The preface thus highlights Kafka’s place within the longer history of the twentieth century, a history which is marked by crisis but also by fortuitous turns. The organisers pay homage to Malcolm Pasley, ‘to whose knowledge and enthusiasm we are indebted both for arranging this exhibition and for compiling this catalogue’ (5). In putting the manuscripts centre-stage and giving the visitor a cross-section of Kafka’s writing styles and media as they evolved over time, the exhibition does indeed bear Pasley’s imprint.[2] As Barber and Jolliffe conclude,

Careful editorial work based on access to manuscripts and printed texts allows an author’s work to be seen in a clear light. We therefore feel honoured to have been entrusted with this archive, to be associated with the edition of the works of one of the most significant authors of our time, and to be allowed to share this with others by means of this exhibition. […] Each age brings its own interpretations of a great writer: it is the duty of libraries to assemble and preserve the evidence on which to base them. (5–6)

The ensuing Introduction, presumably written by Pasley, underlines the collaborative nature of the project, offering thanks to individuals such as Marianna Steiner and Klaus Wagenbach, who provided most of the ‘visual material’ in the exhibition, and to institutions such as the Jewish National and University Library Jerusalem. It also thanks various ‘private owners’ for contributing some of the items on display (8).

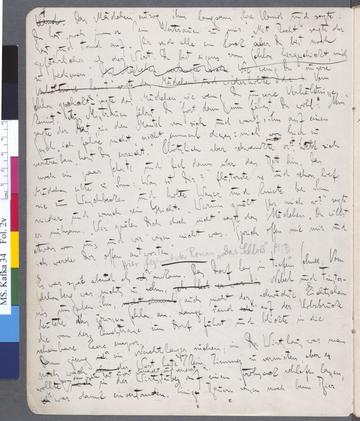

(c) Bodleian Library, University of Oxford - MS Kafka 34, fol. 2v

True to the title ‘From Page to Print’, the Bodleian part of the exhibition offered visitors a chance to view Kafka’s manuscripts alongside first editions of his short stories and short story collections as they were published during his lifetime. Also on display were contextual items such as a photograph of Flora Klug, a member of the Yiddish theatre troupe whose performances Kafka attended in 1912, in her role as a ‘Herrenimitatorin’ (14), and the final listed exhibit, the certificate attesting Kafka’s presence at the Dr Hoffmann’s Sanatarium in Kierling, where he died on 3 June 1924 (33). The literary autographs range from his earliest surviving text, a two-line poem written into the album of his school friend Hugo Bergmann, probably in 1897, to the manuscript of his final short story, ‘Josefine, die Sängerin oder Das Volk der Mäuse’ (1924).[3] Between them, the 80 displayed items give a broad overview of Kafka’s life and work. They include some of his most famous works, such as the ending of his breakthrough story ‘Das Urteil’ (1912), the first and the (unfinished) last chapters of his first novel Der Verschollene (1912/1914), and the opening page of his third and final novel, Das Schloss (1922). Kafka started writing Das Schloss as a first-person narrative but later shifted into the impersonal third-person mode. After he made this transition, he simply went over the preceding chapters, changing all first-person pronouns and verbs into the third person (see image to the right).

The exhibition puts these famous works alongside more obscure pieces such as Kafka’s early prose fragment ‘Beschreibung eines Kampfes’ (1904–1911) and the typescript of his drama fragment ‘Der Gruftwächter’ (1916–17). This part of the exhibition also places his writings in their original context and emphasises their materiality, by displaying the handwritten texts alongside their published versions, as in the case of the short prose text ‘Entschlüsse’, which Kafka first records in his diary quarto notebook on 5 February 1912 and which is subsequently included in his first book, Betrachtung (1912; 17–18).

The second part, hosted at the Taylor Institution and called ‘Paths out of Prague’, is subtitled ‘The Diffusion of Kafka’s Work’ and focussed on his reception in his lifetime and beyond. Its first two sections are dedicated to the resonance of his work between 1912–1924, both in Prague and ‘beyond Bohemia’; a third section, entitled ‘1925–1945: wider contexts’, traces his growing international resonance, as his texts started to appear in Spanish, French, and English translation. Revealingly, a 1942 English translation, ‘Jackals and Arabs’, by Mimi Bartel, in the US periodical New Directions, is accompanied by the editorial remark that ‘the name of Franz Kafka is too familiar to require any comment’ (48). The final section is entitled ‘Since 1945: world renown — with penalties’ (50). It contains more international editions as well as catalogues of Kafka exhibitions which took place in East Berlin in 1966, in Jerusalem in 1966, and in London in 1971. A particular focus, which explains the intriguingly ambivalent title, is on his evolving status in Eastern Europe. Kafka was classed and condemned by the Soviet authorities as a ‘modernist’ alongside writers such as Proust, Beckett, and Joyce, but in the face of his fast-growing popularity in the Eastern Block, as attested by the displayed translations of his works into Czech, Polish, Russian and Hungarian, the regime gradually began to thaw in its attitude towards him.[4] As Pasley comments in the catalogue, the 1963 Kafka conference in Liblice (Czechoslovakia) was the clearest indication of ‘a decisive shift in the official attitude towards Kafka’s work in the Soviet world’ (54).

Though an exhibition on the theme of ‘Kafka in England’ had already taken place in London in 1971, the 1983 Oxford exhibition was probably the first opportunity for a wider public to come face to face with Kafka’s manuscripts. In Oxford and the UK, the 1983 exhibition has also set a precedent for another centenary exhibition, namely one marking the centenary of Kafka’s death, which will take place in the Oxford Weston Library in the spring and summer of 2024.

This is a shortened version of Carolin Duttlinger’s ‘Kafka in Oxford’, Oxford German Studies, 50.4 (2021), 416-427. Find the full version here: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00787191.2021.2021025

Carolin Duttlinger is Professor of German Literature and Culture, Ockenden Fellow in German at Wadham College, and Co-Director of the Oxford Kafka Research Centre, all at the University of Oxford.

[1] [Malcolm Pasley], Catalogue of the Kafka Centenary Exhibition 1983 (Oxford: Bodleian Library, 1983), p. 3. Page references will henceforth be given parenthetically in the text.

[2] See for instance Malcolm Pasley, ‘Kafka’s Der Process: What the Manuscript can tell us’, , 18–19 (1989–90), 109–18; see also the Marbach exhibition catalogue Franz Kafka, ‘Der Process’: Die Handschrift redet, ed. Malcolm Pasley and Ulrich Ott (Marburg/Neckar: Deutsche Schillergesellschaft, 1990).

[3] Kafka, Nachgelassene Schriften und Fragmente I, p. 7. Hugo Bergmann later emigrated to Palestine and became the first director of the Jewish National Library.

[4] For an overview of this shift, see Emily Tall, ‘Who’s Afraid of Franz Kafka? Kafka Criticism in the Soviet Union’, Slavic Review, 35 (1976), 484–503.